Prompting

Prompting is a term for providing your child with assistance to help them to do something. Prompting can facilitate your child to learn new skills and behaviours by providing them with support, so they know how to complete an action or task and what to do next. When your child is learning a new skill, it is important to make sure that they are successful, and to prevent them from practising doing a new skill in the wrong way. If your child gets something wrong the first time, you can prompt them to do it correctly the next time.

Before you begin prompting, you should always give your child a chance to do the behaviour independently in response to the antecedent. You can use a purposeful pause to let your child know that you are waiting for them to respond. For example, you hold out your hand to ask for a turn with the blocks (i.e., holding out your hand = the antecedent), then pause with an expectant look to see if you child will respond independently (i.e., giving you a block, or saying “not now” = the behaviour). A purposeful pause gives your child time to process the request, decide how to respond and then to do the behaviour. Many autistic children need more processing time than we might expect.

However, if your child does not know how to respond independently to the antecedent, we can use prompts to help them to be successful. Examples of prompts include:

- Verbal prompts (e.g., verbally reminding a child to wash their hands)

- Visual prompts (e.g., a picture schedule)

- Gestural prompts (e.g., pointing or nodding)

- Modelling prompt: You demonstrate an action first (while your child is watching), then encourage your child to repeat what you have done (e.g., putting toothpaste on your toothbrush then encouraging your child to do the same)

- Physical prompts: Physically guiding your child to complete a task or action (e.g., using your hand under your child’s hand to guide them to turn on a tap)

Prompts should always be used in the most minimal way possible to support your child to achieve the behaviour and enhance their independence. This means working in the order of least-to-most intrusive prompts. Generally, physical guidance involves more assistance from you than the other types of prompts; too much physical guidance can cause some children to become overly reliant upon an adult to help them to achieve the behaviour. For example, if your child is able to wash their hands, then a purposeful pause may be enough to encourage them to do so, or a verbal reminder or gesture (e.g., pointing) which provides a little more specific support. Physically guiding your child throughout the hand washing process may be too much assistance.

If your child does not respond to the first prompt, then further guidance can be added following the least-to-most principle (e.g., a purposeful pause may be followed by a verbal reminder, then a verbal reminder paired with a visual or gestural prompt). In other words, you should increase the type and level of assistance you give your child bit by bit to give them as many opportunities as possible to be independent. You want to ensure that your child always experiences success and learns to associate the antecedent with the required behaviour.

Once your child can complete the behaviour with your support, then you can reduce your support to increase their independence. For example, waiting a little bit longer and letting your child persevere independently before offering more support. Note however that many tamariki (especially young children) require some level of on-going guidance to complete tasks, such as being reminded to use the toilet or to wash their hands. Tamariki may also forget steps that they had previously remembered on another day, meaning that you may need to adapt the level and amount of guidance you provide on a day-to-day basis.

Step-by-Step Teaching (Chaining)

Many complex play skills and adaptive skills such as self-care behaviours (e.g., washing, dressing, toileting) consist of a series of smaller behaviours and tasks. For example, washing our hands consists of: (1) walking to the basin; (2) turning on the tap; (3) moving our hands under the water; (4) using the soap and rubbing our hands together; (5) moving our hands under the water; (6) turning off the tap; (7) drying our hands with a towel. Each of these tasks may also contain smaller steps. For example, using the soap and rubbing our hands together involves multiple fine and gross motor movements such as squirting the soap and using one hand to wash the other. When your child is learning a new skill or behaviour, it is helpful to break the task down into smaller, manageable parts which can then be taught step-by-step. This process, known as ‘chaining’, can support tamariki to master new skills that may be too challenging to learn all at once. The procedure is as follows:

- Select an Appropriate Goal

Select a specific behaviour to focus on that is about right (not too easy and not too difficult) for your child’s abilities. Make sure the goal is achievable so that your child has some chance of experiencing success early in the process. - Break the Task into Smaller Steps

It is helpful to make a list of each of the smaller steps that your target (goal) behaviour consists of. To do this, you may like to do the behaviour yourself and record each individual step in sequence (i.e., one step should lead to the next). For example, putting on pants consists of: (1) picking up the pants; (2) holding the waistband open; (3) lifting one leg; (4) pulling the pant leg over the foot and up the leg; (5) lifting the other leg; (6) pulling the pant leg over the foot and up the leg; (7) pulling the pants up to the waist. Check that no steps are too difficult (difficult steps can be taught later); for example, if your child is not yet able to manage zips or buttons, then you might start by teaching them to put on pants with an elastic waistband. - Teach each Step

Teach your child each step in the list one step at a time. Note that this means you may need to complete some steps for your child. To teach each step:- Present the steps in a way that your child understands using clear and consistent cues. For example, you may use a visual schedule depicting each step (see ‘Visual Supports’ below).

- Teach your child each step by showing them (e.g., a modelling prompt) and telling them (e.g., with a verbal explanation) what to do. Physical prompts (e.g., hand under hand) may also be useful to support learning especially during the initial stages when your child is first practising a new behaviour, though as noted above, do remember to reduce physical guidance.

- Create lots of opportunities for your child to practise and learn each step.

- Use positive consequences for every good attempt. New behaviours will not be performed perfectly the first time; encourage your child’s learning and their motivation to keep trying by rewarding their attempts at first. As they succeed, ‘move the goal post’ so that they are rewarded for the next part of the behaviour (i.e., your ‘shape’ their ability to achieve an overall behavioural goal). For example, if your child is learning to brush their hair, initially you might provide positive consequences for holding the brush near their head, then for making a brushing attempt, then for brushing in a downwards motion.

- Continue to move through the steps until your child can complete the entire sequence of steps in order (e.g., teaching your child to do the first step independently, then two steps, then three, and so forth).

The order in which you teach the steps can be forwards; that is, starting with the first step (known as forwards chaining) or backwards; that is, starting with the last step (known as backwards chaining). For example, if teaching your child to put on their pants, forwards chaining may involve you getting your child to do the first step of putting their leg through each leg hole while you prompt (see ‘Prompting’ above) or assist them to complete the final steps in the sequence.

With backwards chaining, you might assist your child with the initial steps, but get them to do the final step of pulling their pants up to their waist on their own. While focusing on your child doing the last step might seem strange, backwards chaining is often more beneficial to learning than forwards chaining because the last step can be the most naturally rewarding. For example, it completes the sequence and is often followed by a natural reward (e.g., once your child is dressed, they can play).

Visual Supports

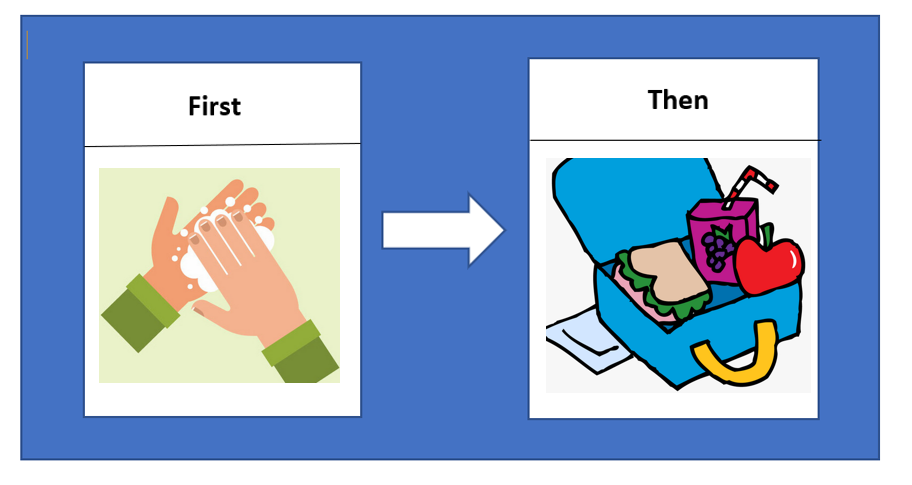

Visual supports are a pictorial representation (e.g., a symbol, photograph, or picture, with or without written words) of what your child needs to do, which can be presented in a variety of formats including as a story (e.g., a social story) or cartoon, picture card (e.g., ‘first-then’ ) or visual schedule (e.g., the steps in a routine; see below). Visual supports can facilitate learning by helping to break tasks into visual sequences and steps to support tamariki to understanding new skills and behaviours. For example, a visual schedule may depict a toileting routine with cartoon images in sequence (e.g., pulling down pants, sitting on the toilet, using toilet paper, pulling up pants, flushing the toilet, washing hands), which may assist a child with following these steps.

Visual supports can be applied to most learning situations and encourage independence by enabling children to refer to visual information as many times as they need to. This can help to reduce adult-led assistance (e.g., children may need to be prompted or supported less by an adult). Visual supports can also help to aid communication (e.g., a child may request food or drink using a picture card). Visual supports are used by almost everyone; for example, the use of a diary, calendar or shopping list are familiar aids that people use to assist memory, organisation, and completion of tasks. The type of visual supports you use will depend on what is suitable for your child.

Visual supports can be paired with other prompts (e.g., a verbal prompt “time to put your shoes on”). Equally, tamariki may use picture cards (or a symbol on a speech-generating device) to communicate (e.g., to request food or drink). First-then (sometimes called ‘if-then’) boards depict two actions in sequence; the first that needs to be completed to access a second, motivating activity or consequence. For example, first wash hands, then have a snack. Visual supports can also be made according to children’s preferences, such as the incorporation of pictures of a high-interest topic or character, to make them more motivating and exciting.

Social storiesTM (Gray & Garand, 1993) are visual supports in story format (e.g., paper/book format with photographs or pictures and written text) that describe situations, social interactions, and tasks that your child may experience. Social Stories provide explicit information to your child about what to expect, what kinds of social behaviours they can try, and what the response might be from the adults and peers around them. They are written in a clear manner from the child’s perspective. Social stories use many descriptions (e.g., “hairdressers are people who cut hair), and perspective sentences (e.g., “the hairdresser likes it when I try to sit still”), with a few directive sentences to help the child to understand behaviours they could try (e.g. “I can try to help the hairdresser by sitting still”). Social stories may facilitate learning by making information more concrete and explicit (e.g., stating what another person might be thinking or feeling, or explaining details the child might not have noticed). They also help tamariki to know what behaviours they could try ahead of time (e.g., “what does the story say you could try next?”). Social stories should be written using pictures and words your child can understand with each page representing an individual step (e.g., each step involved in eating dinner). Make sure to only include details that will definitely happen. For example, if the story says “the hairdresser uses scissors to cut my hair”, but the hairdresser tries to use an electric razor, this could be very upsetting or confusing for your child and undermine the trust in and predictability of the story.